Earlier this week I joined the Reproducibility Symposium at NYU. It was an interesting workshop/unconference with a great group of people. A huge thanks to Vicky Steeves and Juliana Freire that organized the event.

Introduction and Terminology Problems

It started with some nice talks by Jake VanderPlas and Katy Huff. Jake mentioned the issues around terminology, particularly the different conventions for the use of the terms "reproducibility" and "replicability". In some camps "reproducibility" refers to literally doing the same analysis with the same data again, while "replicability" refers to repeating the entire process including data collection. In other camps, these terms are reversed. I mentioned that within the ATLAS experiment we had a similar discussion, complicated by the fact that in an international audience these the sublte differences and connotations associated to these words are not universal. I suggested that at the very least we need to define them, but perhaps we should look for very different terminology to avoid confusion. Philip Stark suggested we use some Up Goer 5 style terminology, e.g. "computational do-over-ability".

The three four pillars of reproducible research

Often in the discussions around open and reproducible science we focus three main types of research products

- the paper: the traditional narrative document, often primary product, DOI is standard

- the data: increasingly appreciated as a first-class citizen of scientific record with data repositories providing DOIs

- the code: recognized as a research product, but the last to be integrated into literature system and given DOI

But even with access to all three of these products reproducing the results or evaluating the methodology can be difficult because software often has dependencies and it can take a lot of effort to prepare the environment. For instance, when Bernard Rous was discussing the great progress they have made at ACM for computational reproduciblity, he mentioned it was still difficult to get the code to run. Moreover, even if the code runs, one might get different results with different versions of the dependencies -- so this is a serious issue for reproducibility. This is not news to people working hard on tools for reproducibility (see DASPOS Container Workshop where Umbrella and reprozip will be discussed). Therefore, I really think we should elevate the environment to be the fourth pillar of computational reproducibility:

- the environment: a critical and under-appreciated ingredient for computational reproducibility

Luckily, there are wonderful new technologies like docker that allow one to package up a working environment so that it can easily be run on other docker-enabled machines -- including a ton of cloud based platforms (eg. Carina). Industry has embraced docker and science can leverage this to great benefit. Two shining examples of this potential are binder and everware that allow one to run Jupyter notebooks (taken directly from a GitHub repository) with a customized environment (packaged as a docker container).

For example, after LIGO discovered gravitational waves they took the awesome step of making an Open Data release with their data and code, but to use it you had to go through a fairly technical installation procedure, which is a significant barrier. To lower this barrier Lukas Heinrich and I (and independently Min-RK) extended made a custom docker image with the necessary software and created ligo-binder (Min's version).

Just as data and software can be reused, these environments can be re-used and extended as well. Moreover, there is already a repository for docker images, it's called docker-hub and you can find ligo-binder on docker-hub. Dockerhub provides usage statistics (think altmetrics) -- for instance, here's a link to the binder-base image that has been pulled more than 250 times. There are even tools ImageLayers to view provenance and re-use of the environment images -- think depsy. What is missing is the ability to issue a DOI to these environments and to elevate them to the same status as a research product. Since it might be hard to get dockerhub to take the responsibility associated with minting DOIs, we could imagine an integration between dockerhub \(\leftrightarrow\) Zenodo similar to the GitHub \(\leftrightarrow\) Zenodo integration.

It is worth noting that tools like reprozip already can save the results of reproducible experiments as a docker container. There is now some effort at NYU to create a hybrid of reprozip and services like Binder.

Libraries and Institutions vs. Domains

We had a good showing from the university Library community and bit of discussion about the role of the libraries and institutional data repositories. I voiced my opinion that it is more effective to build community around a field or domain than an institution. I think it is an inefficient use of resources to develop yet another data repository tool when there already exist many good solutions and what we really lack is vertical integration of various tools to make powerful platforms for open science. Juliana Freire made the point that for communities that don't have well established domain repositories that the institutional repositories play a role. While I agree with that, I also feel that tools like figShare, Zenodo, Dataverse, etc. already provide the infrastructure for data repositories and that the Libraries can be even more valuable in helping guide the domains to use these tools and develop meta-data formats to make it easier to discover and re-use those products. My point seemed to resonate with Karen Adolph who is Director of Databrary, a very successful domain repository for developmental science.

This reminded me of a discussion I had with Arfon Smith a couple years ago where we talked about collecting domain-specific best practices around reproducibility. Imagine a domain specific guide like Ten Simple Rules for the Care and Feeding of Scientific Data together with pointers to tools similar to StackShare or an awesomelist.

Hacking the culture

After a few nice talks, we decided on topics to discuss in break out sessions. The suggested topics were:

- Teaching reproducibility

- "bullying" in open access / reproducibility

- Hacking the culture

- What services should universities and institutions provide to support reproducibility and open science

- tools and adoption

Instead of breaking out into many groups we stayed together focused our discussion on hacking the culture around reproducibility. Philip Stark mentioned his pledge to not review papers that don't present enough information (data, code, etc.) and echoed his motto that "science is show me, not trust me!". He also mentioned the Royal Society’s 453 year old motto, “Nullius in verba” (or "take no one’s word for it") and expressed that we have forgotten that. He conjectured that somewhere around WWII that science went through a qualitative shift in this attitude.

Somewhere in here we discussed AltMetrics (in the most general sense). Philip Stark expressed doubt to their value and warned that we might be propagating the problem of citation metrics by introducing even more metrics. While almost everyone agreed we must take care in how we use AltMetrics, Katy Huff argued that metrics associated to data and code help get the conversation started with faculty committees where these are not part of the traditional metrics. As she put it, they help change the attitude to ``ok, I guess this is a a thing now''. I agree with Katy that these metrics can be useful and with Philip (and almost everyone else) they must not replace pier-review and actually examining a case in detail. I was suggesting that just as their are Coincidentally, I just saw that Indiana University - Bloomington's Faculty adopted a policy on metrics that is largely inspired by the Leiden Manifesto.

Later we had an informal panel / debate on carrots vs. sticks with Rick O. Gilmore, Philip Stark, Meredith Broussard, and myself. The format was fun (thanks Vicky !) as we asked Philip to argue the case for carrots and Rick to argue the case for sticks, in contrast to their more vocal positions. I took on the split-personality of High-Energy Physics.

This discussion was probably my favorite part and a few playful analogies were mentioned as effective ways to discuss the needed change in culture with a skeptical audience.

Analogies

Randy LeVeque made an analogy with mathematical proofs and theorems. People know that their paper with a theorem isn't going to be accepted unless they have a proof, and so people spend significant amounts of time polishing their proofs for publication -- and in the process, the often find problems. So why don't we have the same attitude about code and data analysis?

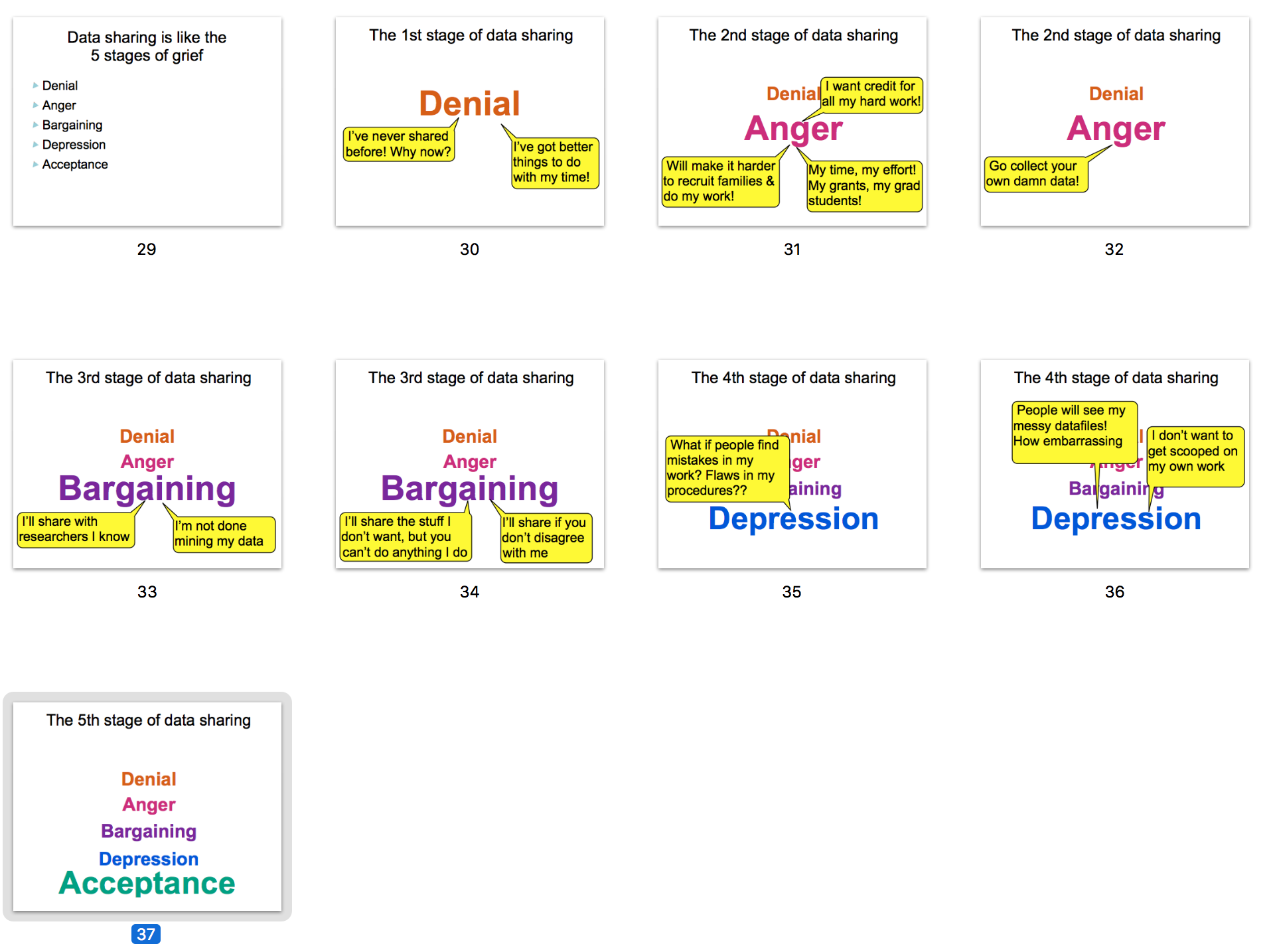

Karen Adolph mentioned Databrary's wonderful analogy with Data sharing and the Kübler-Ross model for 5 stages of grief:

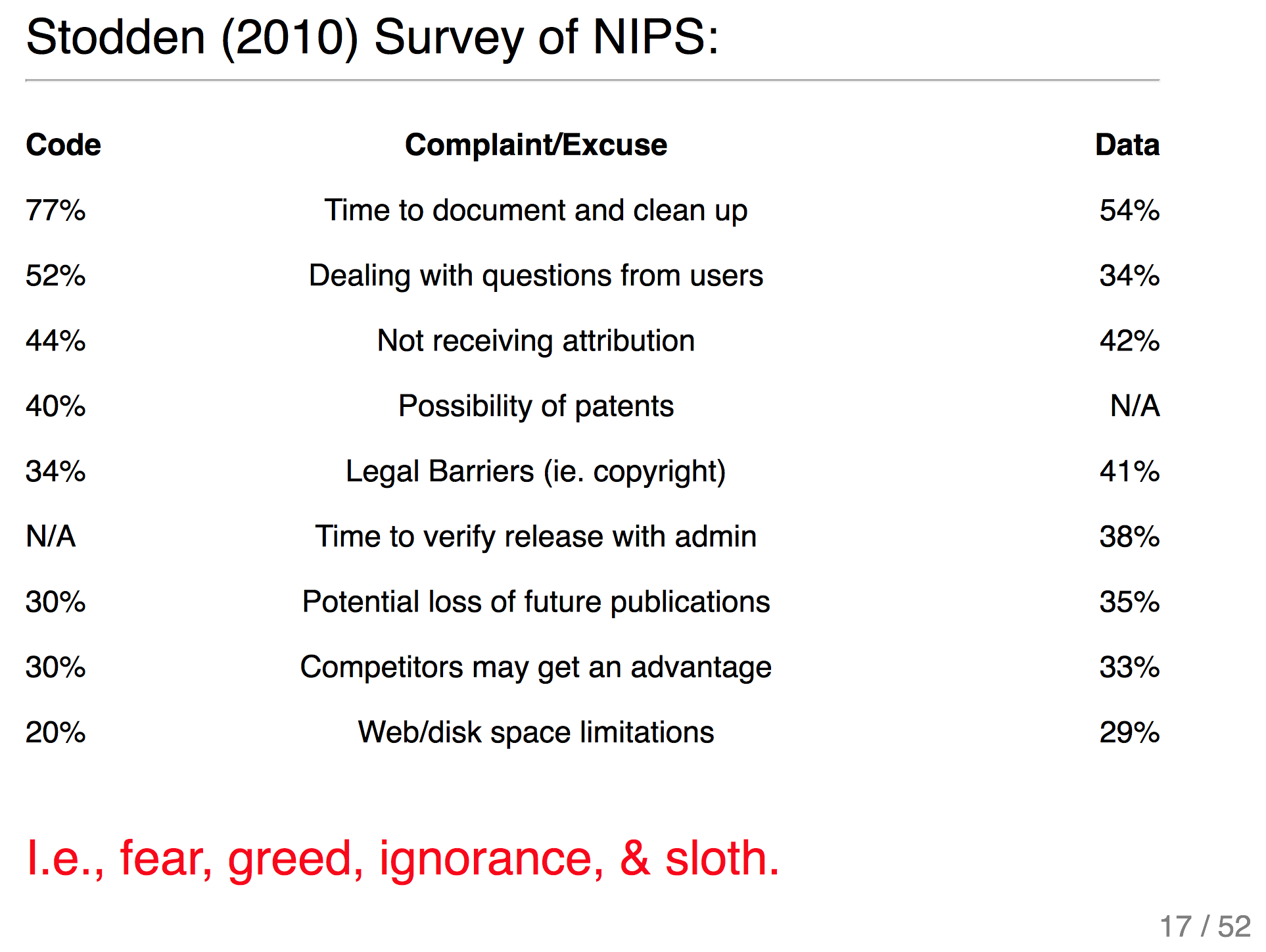

This reminded Katy of Philip's talk where he compared rational for non-reproducible science to the seven deadly sins:

While I liked these a lot, I made my own analogy between trying to convince the recalcitrant portion of the scientific community about the value of reproducibility and the broken conversation around climate change. In particular, I was thinking of the Kahan Study points to polarization as being one of the key barriers to changing opinions (more about the Kahan study). This may or may not be an accurate analogy, but it fits quite well my experiences. If it accurate, then we need different tactics. For instance, focusing on the personal benefits of reproducible science, like improved efficiency.

At this point in the discussion there was a simultaneous consensus that we should put more effort into collecting and presenting evidence about the benefits for open and reproducible science. We hear a lot about the failures, the crisis, and doomsday stories, but success stories may be more effective in motivating individual researchers. It was mentioned that while the first book by UC-BIDS is focused on reproducibility case studies, they had originally discussed success stories as the first in the series. Meredith mentioned that this is a great opportunity to bring in journalists. I think it's a great idea and would suggest that the stories be broken down into three categories:

-

data-focused success: examples of widely cited or re-used data, for example SDSS, Add Health study, Developmental science examples, Kepler exoplanet data, ...

-

science-focused success: discoveries etc. from secondary data (cough research parasites cough) usage specific domains. E.g. Fermi-bubbles,

-

researcher-focused success: (early career) scientists that were successful due to secondary data usage e.g. Doug Finkbeiner, three guys in my office, Swanson's discovery of the migraine-magnesium connection, ...

Ok, well that was a bigger brain-dump than I expected, but it was a wonderful day discussing challenges in promoting reproducible research with many fresh ideas.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus