Despite the reputation of 2016 as a terrible year, it was pretty good for me on a personal and professional level. Many of the ideas that were born during my sabbaticall matured this year. Many of my collaborations also flourished.

The 750 GeV Excess

The year started with a bang with a bumplet in the LHC data -- specifically the 750 GeV diphoton excess. This led to lots of excitement in the field and in the media. I was interviewed by the New York Times, Vox, and NPR's Here and Now about it.

One of the concerns in interpreting the significance of that bump in the data was that we perform so many different tests of the Standard Model that we expect to see big fluctuations occasionally. We often call this the look-elsewhere effect. Conventional wisdom is that this effect goes away because we have two experiments seeing the same thing. While it's true that having two experiments reduces this effect, it doesn't go away entirely. I was thinking about all of this early in the year and came up with a nice way to connect Gaussian Processes and the look-elsewhere effect .

The excitement around the bump was extraordinary, there were more than 100 papers on the subject by February. In March there was a lot of introspection in the field about this phenomena. I decided to write an April Fools Day paper about it. It's full of subtle physics and statistics references -- so while it's not at all accessible, I'm pretty happy with it.

Unfortunately, by August the 750 GeV diphoton bump had disappeared with more data. André David kept track of the number of citations throughout the year.

#Run2Seminar 1st (only?) anniversary.

— André David (@DrAndreDavid) December 15, 2016

3 clear #750GeV #diphoton phases:

- Inflationary Xmas.

- Moriond steady state.

- Post-ICHEP flatline. pic.twitter.com/7UUQTrTo5P

Carl and likelihood-free inference

One of the most significant outcomes of my sabbatical at UC-Irvine was this idea that we can use classifiers from machine learning to approximate an intractable likelihood function and perform inference. While the term is unfamiliar, intractable likelihoods is one of the defining challenges of data analysis for experimental high-energy physics. Our field has developed a lot of strategies, but we have not formulated them in this way. I've found that formulating them this way really helps clarify many issues and makes it clear that there are ample opportunities for improvement. Moreover, many other scientific disciplines can be formulated in this way, which facilitates communication between the scientific domain and the statistics / machine learning communities.

In 2015, I started to focus on this topic of likelihood-free inference and wrote my first non-physics paper. The idea was there, but it needed to be rewritten and supported by examples. In late 2015, I hired Gilles Louppe, who has a PhD in Computer Science and focuses on machine learning. He started working on Carl, a toolbox for likelihood-free inference that implemented the techniques in the paper. I'd already been working with Juan Pavez on examples, and I invited Gilles and Juan as authors for version 2 of the paper. That was our main focus in February and March. In the process the core idea really matured and we made connections to many different topics, including generative models, importance sampling / reweighting, and adversarial training. These all ended up being themes of my talk at NIPS in December.

This set of connections has fascinated me for the last year. So many different ideas come together under one umbrella. https://t.co/eeiVP32ASo

— Kyle Cranmer (@KyleCranmer) December 28, 2016

Major progress on long-term projects

This year also saw progress on a number of long-term projects.

Recast & Analysis Preservation

Back in 2009, Itay Yavin, James Beacham, and I went back to old ALEPH data and looked for the Higgs there before it was discovered at the LHC. There was a nice Wired article about that story. It also initiated my interest in data and software preservation, open science, reproducibility, etc. In particular, in 2010 Itay Yavin and I proposed Recast -- a system for reinterpreting the results of searches for new particles. In early 2012 we launched a beta version of the Recast front-end website. Of course, the Higgs was found months later and that distracted all work on Recast for a few years. In 2015, my student Lukas Heinrich picked it up, and started to work on the back end that does all the heavy lifting. The ATLAS collaboration also formed a small task force to look into issues around analysis preservation and reinterpretation, which I served on. Simultaneously, the group that produced CERN's Open Data Portal started putting more emphasis into the CERN Analysis Preservation project. We've been working with them since the beginning and now the entire effort is making great progress. Along the way, we realized that yadage, the tool Lukas developed for the Recast backend, provides a generic, flexible system for distributed workflows, where each processing step can be containerized (eg. with docker) independently.

When LIGO announced their discovery of gravitational waves in February, they took an important step in releasing the data and code related to the discovery. Lukas and I quickly dockerized the environment needed for their Jupyter notebook and made ligo-binder, which you can run in your browser with no installation.

All of this work on reproducible workflows ties in nicely with likelihood-free inference, because in likelihood-free inference, you need to encapsulate the simulation pipeline. I wrote a bit about this earlier after our Reproducibility Symposium at NYU in May.

A huge boost to the project came in September when we found out that the NSF approved an extension to the DASPOS project to further the development of Recast and deploy the yadage workflow execution engine as part of the CERN Analysis Preservation project. With this funding, we are working with Heiko Müller (a research engineer as part of the MSDSE / NYU CDS) and Tim Head (previously on LHCb).

HEPAP

In April I went to Washington DC and was sworn in as a special government employee to be a member of the High Energy Physics Advisory Panel (HEPAP), which has advised the Federal Government on the national program in experimental and theoretical high energy physics research since 1967. We discussed the planning and progress in the field since the P5 Report.

INSPIRE & HEPData

This was also a big year from INSPIRE and HEPData, two important parts of the cyberinfrastructure for high energy physics. I am on the advisory board for both of these projects and work with them quite closely. I was part of the discussion that led to the decision to migrate the legacy version of HEPData to the Invenio platform that powers INSPIRE, the CERN Open Data Portal, Zenodo, and other sites. Lukas and I worked with Eamonn Maguire and others in the HEPData team as part of this migration. It was a real pleasure to work with Eamonn, who makes awesome products and has a great design sense. The new HEPData was announced in April and Lukas presented it at CHEP in October.

In May we had an I went to SLAC for the INSPIRE advisory board meeting. INSPIRE has also been migrating to a new version of INVENIO and the site will be much nicer. There is a preview of the site at qa.inspirehep.net. During that meeting, I also presented some vision for how INSPIRE fits into the cyberinfrastructure priorities at the NSF and various foundations. I've also initiated some discussions with the NYU library about getting more directly involved.

ATLAS Week

Despite warnings from some close friends, I put in a proposal to host ATLAS week at NYU. We won the bid and that started the incredibly time consuming process of planning the meeting. Luckily, I had a lot of help from Connie Potter, Petya Lilova, Jennifer Morral, Andy Haas, Allen Mincer, and Ben Kaplan in organizing it. Organizing ATLAS week consumed essentially all of June and probably another month integrated over the year. Luckily, it went quite well. We had more than 300 people for the first ATLAS week hosted in the US in more than a decade.

Data Science @ HEP

We organized a Data Science @ HEP workshop at the Simons Center for Data Analysis in July immediately after ATLAS week. Gilles Louppe and Juan Pavez flew in, and several NYU machine learning experts attended including Rob Fergus, Kyunghyun Cho, and Uri Shalit. This is where I first met Uri and I was grateful for how engaged he was during the workshop. That has started an ongoing discussions about machine learning and inference.

During that workshop the physicists presented a few problems and data sets that could be used by the machine learning community. These ended up seeding several of the projects I mention below regarding the Masters program in Data Science. Rob and Kyunghyun made some nice suggestions for the 3d reconstruction of the liquid argon time projection project.

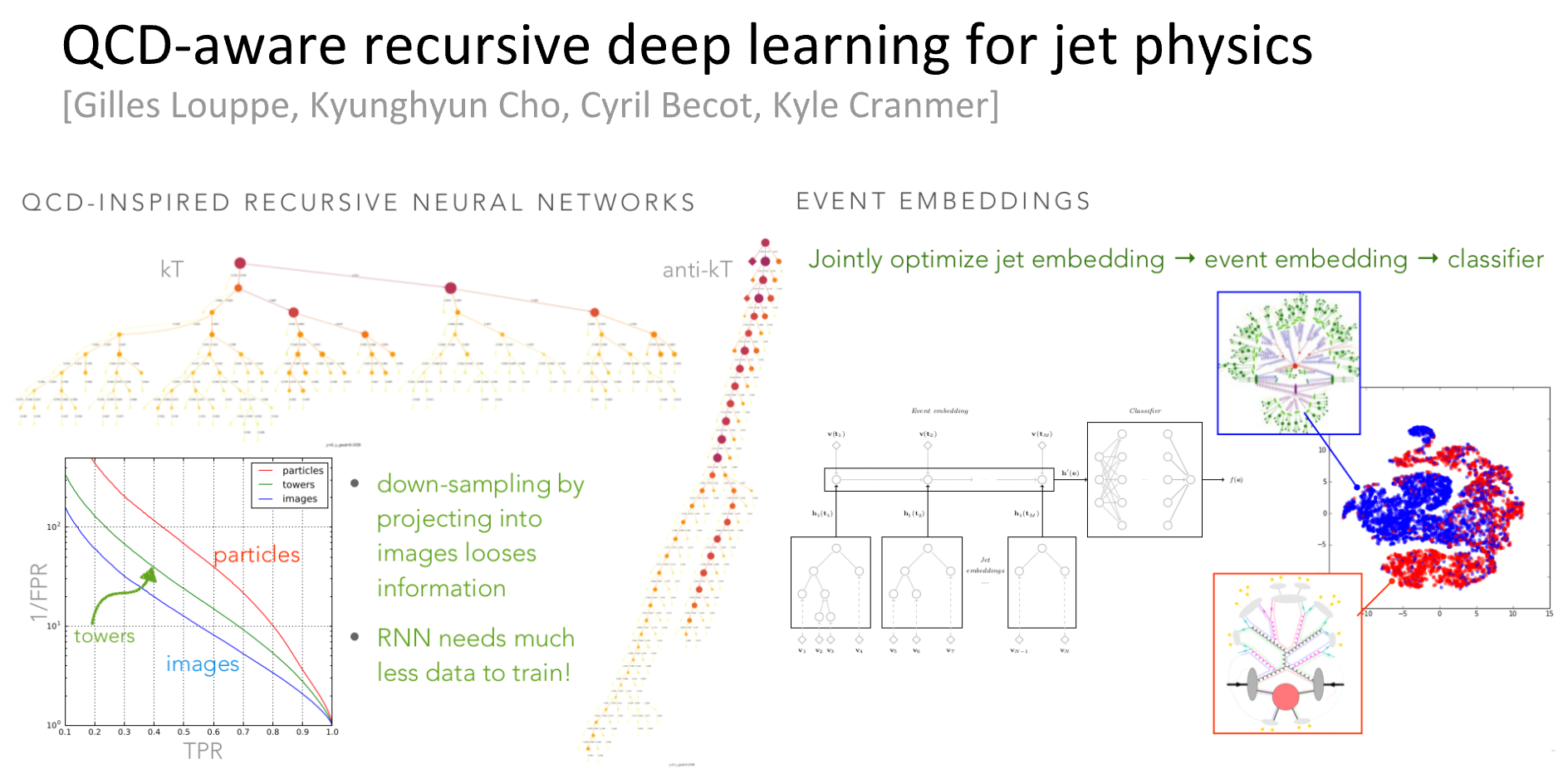

"Jet Sentences", QCD-Inspired Deep Learning, Jet Embeddings

After the workshop in July, Kyunghyun and I had a few discussions about deep learning for particle physics. Kyunghyun does a lot of amazing work with natural language processing, and I spent some time trying to learn about those techniques. He drew a picture that I left on my blackboard for more than a month, which gave birth to an idea and a new collaboration

One of the early successes in applying deep learning techniques to particle physics problems was related to `jet tagging'. In jet tagging we want to classify a spray of particles known as a 'jet' based on its progenitor. The first approach, known as Jet Images, treated the energy deposits in our detectors like an image and then used fairly common deep learning techniques. While this was able to match or outperform the traditional approaches based on variables based on our understanding of the strong force (aka Quantum ChromoDynamics or QCD), it felt somewhat unsatisfactory to me. First, it required discretizing the energy deposits into a regular grid, which both looses information and is not an accurate reflection of our detector geometry. Secondly, the traditional variables have theoretical properties, which the machine learning approaches don't because they don't know anything about QCD.

The idea that emerged was to make an analogy with natural language processing and jet reconstruction algorithms. In the analogy:

- word \(\leftrightarrow\) particle

- sentence \(\leftrightarrow\) jet

- parsing \(\leftrightarrow\) clustering history of a jet algorithm

The idea was that we would use the clustering history as the topology for a recursive neural network. Those jet algorithms know a lot about QCD and have nice theoretical properties. Gilles Louppe worked with Cyril Becot to ge the jet algorithms integrated into the pipeline, and Gilles coded them up and came up with some clever ways to efficiently train these QCD-inspired recursive neural networks. We are now done with the studies, and should have a paper out in early 2017.

Physics Track in the Masters of Data Science

As part of the Moore-Sloan Data Science Environment at NYU, I spend quite a bit of time thinking

about how we can develop a sustainable resource of data science in academia,

which can focus on scientific problems.

The Master's in Data Science at NYU's Center for Data Science has been very successful, with more than a thousand applications less than 100 spots.

In April I had the idea of creating some sort of hybrid masters

program between data science and physics. I proposed the idea and got a lot of encouragement to develop it further.

The physics department gave leave from teaching in the fall to make it into a reality. We ended up creating a

physics track in the existing Masters of Data Science with special curriculum requirements. In addition to the

core data science courses, the students that enter this track will take two physics courses and spend two semesters

doing research on physics-related topics. Faculty in the physics department have so many ideas for data science projects

relevant to physics research, but typically these projects are either seen as a distraction for a typical PhD student,

or the physics students don't really have the right skill set. In addition to being increasing the research capacity

of the physics department, this program will help differentiate the graduates. Physicists are highly sought after

in data science roles, so perhaps the students that go through this track will have a competitive advantage.

The Physics Department, the Faculty of Arts and Science, and the Center for Data Science approved the track in September. The program will start in the fall of 2017 and we are taking applications now.

As a soft-launch for the Physics Track in the MS in Data Science, I proposed a few Capstone projects to the current masters students. Since the students don't have any particular physics background, it was also good practice for posing problems and preparing data in a way that does not require a lot of domain expertise. I was surprised that five groups picked my physics projects. So while I wasn't teaching in the fall, I was advising 15 masters students! I was impressed with the progress they made in one semester. The tweet below starts a thread that gives a short description of those five projects.

This semester I advised 5 physics-related Capstone projects for @NYUDataScience Masters Program. https://t.co/IwpFfVwYlx (1/n) pic.twitter.com/9FTnuALBoa

— Kyle Cranmer (@KyleCranmer) December 16, 2016

Higgs Effective Field Theory & Information Geometry

The first science driver of the P5 Report is Use the Higgs boson as a new tool for discovery. One of the primary strategies for doing this is to make precision measurements of the Higgs boson's properties. The Higgs boson of the Standard Model is completely specified, so measuring its properties requires thinking of the Standard Model as a specific point in some larger space of theories. The most theoretically attractive way to do this is in the language of Effective Field Theory. There are entire conferences devoted to Higgs Effective Field Theory these days, so a breakthrough in this direction is very important.

Most of the strategies for making measurements for Higgs effective field theory are based on picking one or two particularly good variables (observables) that are sensitive to deviations from the Standard Model. Ideally, we would be able to use all the information in an event for these measurements, but that is hard because the detector simulation leads to intractable likelihoods. This takes us back to the earlier point about likelihood-free inference. For the last year, Juan, Cyril, Lukas, Gilles, and I have been working on applying carl and our likelihood-free inference techniques to Higgs effective field theory. I talked about this program of at seminars and colloquia at Yale, MIT, Rice, SLAC, Johns Hopkins, and the Aspen Center for Physics. I'm pretty excited about it, but there's more to do!

One of the obvious questions that arises when we start talking about a rather complicated sounding technique is ``how much do you gain?'' It's a good question, but we didn't really know the answer to it since it requires that you do the Higgs EFT analysis both ways... and that's a lot of work. Fortunately, while I was lecturing at TASI 2016, Johann Brehmer approached me saying that he would be interested in pursuing this. We had talked about it over beers when I was lecturing in Heidelberg in 2015. In particular, we had talked about starting with a simplified scenario where we idealize the detector response. This is common in 'phenomenological' studies by theorists. Part of what made the project so compelling is that we brought in ideas from Information Geometry. In this setup, you have a statistical model \(p(x|\theta)\), where \(x\) is the data and \(\theta\) are the parameters of the model to be inferred. With information geometry, you get to think about the space of the theory in terms of geometry. And there are some powerful theorems that relate this geometry to parameter estimates with minimum variance. Information Geometry has been a passion of mine for more than a decade, but this was the first time I was able to do something really interesting with it. We had a nice collaboration with Tilman Plehn and Felix Kling, but I think it's fair to say that Johann was really the force that pushed the paper Better Higgs Measurements Through Information Geometry out the door.

Learning to pivot

One of the major obstacles to the adoption of machine learning techniques in the sciences is the presence of systematic uncertainties. In particle physics we typically use our simulation to create synthetic, labeled data for training. The simulations have a number of adjustable knobs that can be adjusted to describe the data. The settings of those knobs aren't known exactly, and that leads to systematic uncertainties.

Typically we use some nominal settings for training and then propagate these uncertainties through a fixed classifier. However, that approach isn't optimal. Ideally, the training procedure would know about the sources of uncertainty and lead to a classifier that is robust to these sources of uncertainty. Gilles Louppe, Michael Kagan, and I figured out a way to do that by using a new technique in machine learning: adversarial training. We called our technique "Learning to Pivot".

NIPS

The culmination of my professional year was a keynote talk at NIPS 2016 in Barcelona. NIPS is considered the top conference in machine learning, and in recent years it has grown exponentially. This year there were about 6000 people registered!

This was a challenging talk to give, not only because of the enormous audience, but also because it is not my core subject. It was an amazing opportunity to communicate the interesting problems in particle physics and the opportunities for machine learning and artificial intelligence to radically impact our field.

On the first day of the conference, I attended excellent tutorials on variational inference and Generative Adversarial Networks. I wanted to make references to both of these topics in my talk, and during the tutorials I had a profound realization. I realized that some of the recent work in those areas provides a way to unify generative models and exact likelihood-free inference. It was an odd time to have a big idea because I needed to be finalizing my talk. But it was also very relevant for my topic. I discussed it with Gilles and then during the speaker's dinner on Tuesday night, I discussed it with Ian Goodfellow and Shakir Mohamed. Ian helped get me in touch with Durk Kingma. My talk was the next morning, but it was really dominating my thoughts. I added a row in a table that made reference to the idea, but I didn't spend any time discussing it.

I felt that the talk on Wednesday morning went pretty well. My talk was too long, and I knew it. I sacrificed a lot of the meat and details for the over arching message, and I think that was the right decision. I posted my slides to figshare, and I was astounded that in less than a week it was downloaded more than a thousand times!

After the talk, I took advantage of my time there to talk with Ian, Durk, Max Welling, and Neil Lawrence. I was so compelled by these new ideas that barely sleeping. I also had a fascinating discussion with Frank Wood about probabilistic programming and likelihood free inference. On Sunday I spent the day walking around the city with my former student Sven Kreiss on his Birthday. We visited the Sagrada Familia during the sunset and it was spectacular. I left Barcelona knowing that NIPS2016 was a transformational event for me.

Here are the slides from my talk at #NIPS2016 on machine learning & likelihood-free inference for particle physicshttps://t.co/pvmPCFexyZ pic.twitter.com/72EDdwVnXE

— Kyle Cranmer (@KyleCranmer) December 7, 2016

DIANA

Immediately after NIPS our DIANA group had an end of the year meeting.

Gilles, Lukas, and I put together some slides reviewing the year and our

future plans. The various threads

of my research have always been part of a bigger picture, but

for one of the first times I feel like the various threads

of my research are really coming together. It's a good feeling,

and I'm looking forward to 2017!

Happy New Year!